Silver Threads

Still walking, still waking

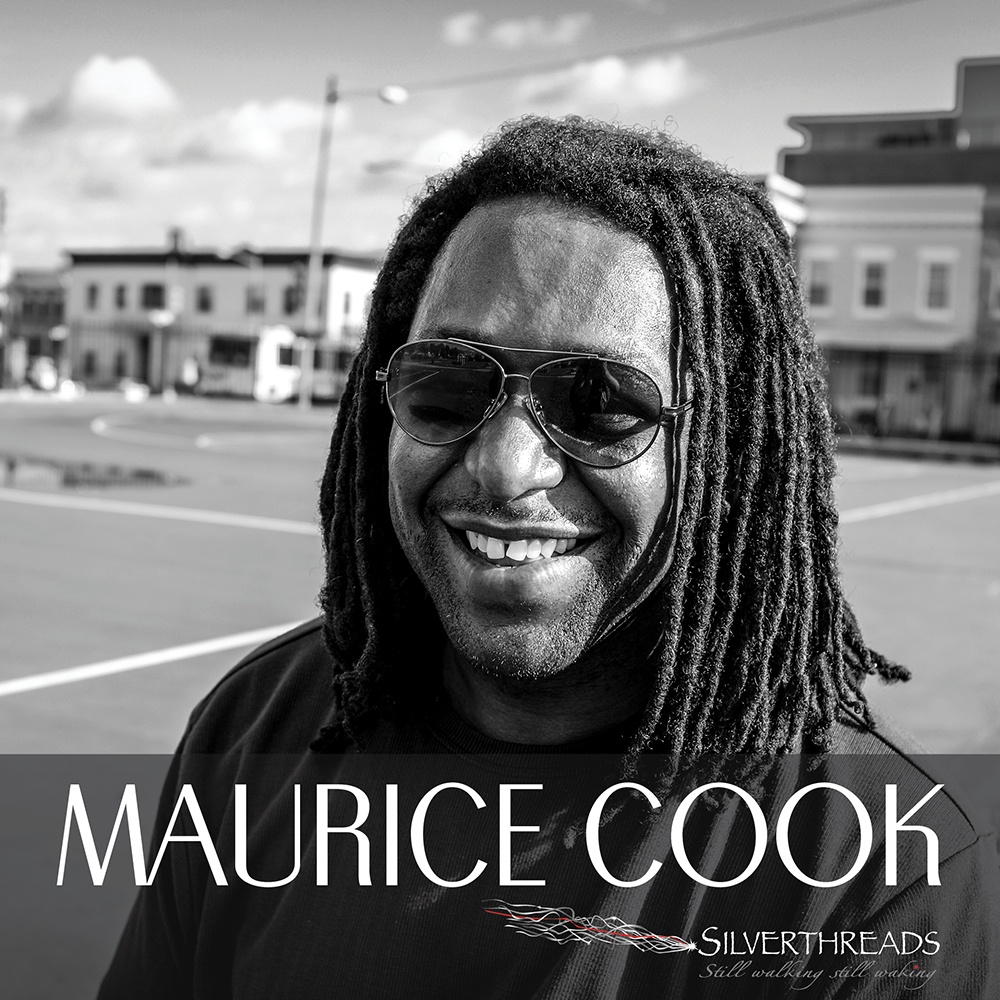

Growing Beautiful Flowers - Maurice Cook

“We grew beautiful flowers during Jim Crow. And we need those skills back.”

Maurice Cook is a grassroots activist, a national organizer, historian and a fierce educator on all matters related to the liberation of Black and brown people in Washington DC and around the world.

He joins the Silver Threads podcast to talk about the power of community care, invading white-only spaces, nuance in our worldviews, hope for the future and more.

BIO

Maurice Cook is a grassroots activist, a national organizer, historian and a fierce educator on all matters related to the liberation of black and brown people in Washington DC and around the world. Whether he’s rallying thousands to march for justice or working behind the scenes to build coalitions that affect change, Maurice’s passionate heart is always at the lead.

A devoted advocate of our nation’s black and brown children, Maurice fights tirelessly against the occupying forces of capitalism, educational inequality, gentrification/displacement, criminal justice abuse, and white supremacy. He understands that the power sits with the people and brings his voice to all places and forums where a deeper understanding of liberation and the gathering of resources is the next right step to turning the tide–whether it’s the classroom, the playground, the boardroom, a council meeting, an academic panel, a town hall meeting or the city streets.

A seasoned speaker and beloved public advocate, Maurice does this work to fulfill the legacy of his mothers, aunts and grandmothers who instilled in him the conviction and perseverance to do everything in his power to bring justice, parity and reckoning to all those who would align with the systems that are hurting all of us. He stands in the gap as a thought leader but more importantly as a nurturing and protective presence—in church basements and community centers where safety is paramount and togetherness is the cure to the hate that seeks to intimidate and undermine our collective confidence in a more just world.

Find Maurice on Twitter at @mcSYCdc.

About Silver Threads: still walking, still waking

carla bergman and Eleanor Goldfield interview long term organizers about their watershed moments, what they have learned along the way, and how they maintain their hope on this path; dreaming and building emergent worlds for a present and future that is anchored in justice and freedom for all.

Episode Transcript

Eleanor

Hey, and welcome to Silver Threads. I’m Eleanor Goldfield. And this is the show where we trace our present path through the people and stories of the past as we ourselves, long-term activists, learn about each other, from each other and continue to walk, continue to wake. So, as I said, I’m Eleanor and this show is done with my co-host, carla bergman, but I’m just doing the intro for this podcast today. So I will keep it relatively short and sweet. Because the good stuff comes after the introductions. We all know that. So this week, or this podcast, we have as our guest, we have Maurice Cook, who’s a grassroots activist and national organizer, a historian and a fierce educator on all matters related to the liberation of Black and brown people in Washington, DC, but also around the world. And I met Maurice a few years ago. And since then have been, I continue to be impressed and blown away by his grassroots organizing, and his humility in the face of learning new things and organizing, but also his fierce pride and unapologetic moves to, as he has told me in the past, invade white-only spaces to make room predominantly for the youth that he works with, as a founder of the organization Serve Your City. And, as I’ve found in the, in the past, with so many organizers, and activists. And, you know, it can sometimes almost sound trite or cliche, but it’s because it’s true. Maurice does all of this from a deep place of profound love for his people, for his community, and for the ideas of what could be. And so without further ado, I would like to share with you some conversation between myself, carla and Maurice Cook,

Maurice

If I were to identify something that was a transition for me, it would have to be It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back. And so that was a Public Enemy album, circa 1988. And that album dropped during my freshman year at Howard. And there was a lot going on politically, socially, at that time, but of course, you know, it’s a coming-of-age, you know, your freshman year in college, right. And me going to school, in a white majority county, in Montgomery County, you know, having, you know, relatives here in DC and growing up, you know, going back and forth from my, you know, the county experience, and comparing that to my DC experience. Because I had relatives here and I had to stay here also in the city. And the two experiences were so crucial for me, because, you know, I used to run to DC when I was a young person, when I had the ability to do it, you know, autonomously and independently as a teenager to get in trouble. I would come to the city to be anonymous. Because in the county, being a good-looking smart Black kid, you stick out, right? Whereas in the city, I was invisible. And I loved the freedom of being invisible. Because it was such a, you know, majority Black place and, you know, eyes, the white gaze wasn’t always on top of me, if that makes sense. And so, you know, everyone, people would ask me, why are you going to go to the HBCU, you know, when you have the opportunity to go other places? When I think about it, even though I couldn’t articulate the answer. I knew I wanted to escape that white gaze, and I want it to be free of it. Because it was so stifling and limiting and dangerous, really. And so, I think the combination of that album, and you know, I guess it’s really hard to explain. We hadn’t had radical, real radical Black music for, you know, a generation, since the, you know, the early ’70s. And we hadn’t really had it in, in rap or hip hop, at that time at that level. And so that was a very crucial album, that really radicalized me and, and, and just going to Howard at the same time, and then experiencing the rebellion in LA after the beating of Rodney King, you know, that was all my freshman year in college. Tough stuff.

carla

Wow, I love that you started off talking about art or music as a watershed moment. I think that will really resonate with a lot of people. But sort of connecting that to what we’re asking you here you know, what was, when you started organizing, or being part of a larger movement, was there someone or a thinker or an activist who inspired you as well? Or that you learned from?

Maurice

Yeah, I always give this credit to my family members, because, you know, they did the little things that add up to big things. And, you know, I grew up hearing the stories. My mother and grandfather spent time in Resurrection City in ’68. Resurrection City was here in DC on the Mall, when a tent encampment was popped up of a bunch of poor people in response to the oppression of capitalism. And they were absolutely punished for it by the State and the weather. There was a torrential downfall that summer, which has made it a sloppy mess. But this was such a watershed moment for my mother, as a teenager, she was a teenager in ’68. And this was probably the most quality time she had with my grandfather, just the two of them, you know, one-on-one. And so when she spoke of it, it was very interpersonal. But she also tied in the political and the structural in that story. And so she really kind of, I would say, sparked the fire of recognizing and just like any Black boy, I mean, and I’m growing up as a Black boy with his father in prison. And so, I’m growing up normalizing the structural, you know, oppression of Black men, you know, as a child. Being, you know, I am part of that latchkey generation. I don’t know if you guys remember that. But yeah, the latch-key generation where we would come home, because my mother was working two jobs, and we would come home by ourselves, as children, my brother and I. And so being Black is always, you know, political. In a nation in a society, in a country where we probably were not supposed to survive, right as a commodity. And I can accept that. So there’s no non-political space for Black people out in the open public. And Black parents, specifically Black parents of my mom’s generation. So my mom experienced the trauma of the transition between segregation and integration. And that was a traumatic, traumatic experience that seeps out more and more as she gets older, specifically, with what’s going on now, because she’s being re-traumatized. And so I’m experiencing right now my mom being re-traumatized over events that occurred 60 years ago. That’s what we’re living with right now. From the generation, that quiet generation who were integrated, the first Black people who were integrated. During the time when, when my generation was coming up, our parents, you know, they hid this pain from us. Because I’m part of that promise generation, the first Black generation, that normalized integration. And so I’m giving you a lot of context here, because I can, now that I’m old enough, I can kind of see, I can see kind of our political placement of where we are currently right now, because of this context. And it took time to understand and kind of see the full scale of it. And so, I would say, my mom, and of course, my grandmother, you know, who was extremely influential, you know, to me, and just taught me how to organize people. You know, taking a little bit and making it into growing it into a lot. I always give that credit to my family. You know, where, sure, I could say so, so many, you know, revolutionaries. But to be honest, it’s so revolutionary to believe that your Black children have an opportunity for living a healthy, healing life in this country.

carla

That’s beautiful.

Maurice

Well, my grandmother would come back and hurt me if I didn’t give her some credit. [lauging] This is one thing. Yeah, I’m afraid.

carla

Don’t mess with the matriarchs.

Maurice

That’s right, exactly.

Eleanor

So kind of picking up on that thread of like, there’s no non-political space for a Black body, like, in this system. With that, like, what does radicalism mean to you? In relation, like, especially in a place like DC that is both like, the seat of empire, but also a very localized fight?

Maurice

Yeah, no, I that’s such I love the way you frame that to you know, the seat of Empire. You know, because, you know, Eleanor, I’m telling you, I didn’t look at DC that way growing up here. No, because by the time I came into consciousness, and I would say, that was around probably ’75, ‘ 76, this city was so powerfully Black. It was so beautiful. And, and this is at the, I would say, the height of the Black Power movement, right. ’75-’76. And all I can remember were, I can remember a lot of things, but I remember everyone called me “eh, Youngblood,” you know, I remember being called Youngblood, you know. I just remember how proud — I mean, I have that in me, like the pride of saying, you know, we just got through something amazing. And we have a chance for Black empowerment, Black autonomy and, and Black excellence. And there came that, the Black civility politics, and the growth of a Black middle class, which I’m a beneficiary of, as well. I’m a beneficiary of that, too. Because that created opportunities for Black people to be in the civil service, to purchase, you know, homes and be part of the home ownership class, and to be the gatekeepers to other opportunities. And so I tell people, I tell people all the time, you know, my first jobs in DC, I didn’t talk to any white people. I just dealt with Black people. And I normalized that. I thought that was everywhere. And so in a way, while yes, and then we you know, this is all juxtaposed against Reagan and reaganomics and Reagan’s anti-Blackness and Reagan’s anti-Black policies, and the, what do you call it, the push and pull, the response to the civil rights movement. What do you call that?

carla

Backlash?

Maurice

The backlash, right. The backlash. Yeah. Soc the jobs started to decrease. They cut federal government jobs. They stopped spending money on federal programs, which, inevitably would affect the city. They tightened their grip on DCs home rule. They created a control board. So that’s where the seed of the Empire kind of comes into. But you notice how it’s from a localized frame, if that makes sense.

Eleanor

So I kind of want to dig into that for a second, because I know we hung out this weekend. I mentioned Margaret Kimberley, and you were like, “oh, love her.’ And her comment about like Blackness leadership and how when I interviewed her once, she said, “I never wanted a Black president, because I know what you had to do to get a Black president. And that’s turn your back on the Black community.” So like as a community organizer, do you feel that like, in terms of your radicalism, is it like, let’s fight to have Black people at office? And then they end up like, you know, a Mayor Bowser? Or is it like, you know, fuck it, let’s make the government obsolete, rather than try to like overthrow it, kind of thing.

Maurice

It’s so nuanced and such a tough conversation. I mean, let me speak for myself, as someone Black. There’s a deep hole of scarcity and low expectations within me, being Black in this country. We’ve got a lot of L’s, too many L’s, too many losses. And the fact… I didn’t believe that this country had the type of spirit to ever elect a Black liberal to the office of President. I didn’t believe it. It shocked me that Barack Obama was elected. Shocked me. And, symbolically, I mean, unfortunately, because of that level of scarcity that I personally feel, I’m gonna go ahead and make I think, a safe bet that many other Black people have this level of scarcity, they feel this level of scarcity. This symbolic co-option into the society is extremely significant. So I can’t devalue Barack Obama’s election and the symbolism of it. I can’t do that, because that would be disingenuous. But then there is this. The fact that his election is used as a way to deflect from the structural disparities and inequality of Black people. It’s used as a weapon. And it just speaks to what we now can talk about as the co-option of the civil rights movement into the very system that created the need for the civil rights movement in the first place. We know that the system uses co-option as a tactic to mitigate and muffle and silence any resistance. And we have to be aware of that and we have to strategize in that we have to build more collectives, less individual individuals, less leaders and more leaderful organizations and coalitions. We just have to be aware of that. Yeah, and the misleadership class. I mean, it’s so real here in Washington, DC. And it’s extremely painful. I mean, these are tough conversations. Conversations, that we have to really develop the language to speak to it publicly, in a real public way. But you know, it’s hard for Black people to speak to each other publicly, because then, you know, white people get in their feelings. And all of a sudden we lose jobs. So how do we have this public conversation with our elite middle class family, about their gatekeeping and their co-option into the institutions that hurt the majority of us,

Eleanor

You’re listening to Silver Threads, part of the Grounded Futures multimedia platform. For more information and to donate to our totally ad-free show, check out groundedfutures.com. You can reach out to us with thoughts and suggestions at [email protected]. You can find out more about our host Eleanor via artkillingapathy.com, and our host, carla via joyfulthreadsproductions.com. And now, back to the show.

carla

I really wanted to shift to your work with young people. Thinking about, you know, as a historian, and that you really hold at your centre, it sounds like the work of the people of the past, which is just beautiful. And starting with your family. I read on the Serve Your City website that everyone has the ability and obligation to become directly engaged, improving the lives of youth and families in need. I’m just curious about kind of connecting this Reaganomics, neoliberal trend that started in the early ’70s. From the right that we’re still fighting today, up to Obama, to all this. But you’ve been saying so far, but connecting this to the young people you’re working with? And what’s what’s that work look like? What do you do? Is there hope there? I’m going to leave it there, let you say.

Maurice

This is the thing. You know, if you bring a historical perspective in there. I was telling the owner this the other night. I have my one foot in the 20th century and one foot in the 21st century. Actually, I probably have 1.5 in the 20th century, let’s be honest, right, and dragging that foot into the 21st century, dragging slowly. But I got to see the old world. And I got to see the end of Black, forced autonomy. So before we could depend upon the government, to maintain a basic subsistence level for Black people.,I know people may be shocked by this, but we used to have to take care of ourselves. I know that sounds crazy. And we did a hell of a job doing that, given all the forces that were against us, and the very little means we had to do that. And we did a great job. And Serve Your City is, to me, in my mind, it is an acknowledgment, and a celebration of that. We had everything we needed in order to make sure everybody had something. We didn’t accept people who had something while others had nothing. I remember this world and Serve Your City is about making sure that our youth and our kids that they have something. And in fact, I take it further. The radicalism goes into I make sure that they have exactly the same. That’s the world, you know, I want to build. Right? And that comes from the pain of every time somebody told me, ‘no,’ because I didn’t have enough money. They made a mistake telling me ‘no,’ that I didn’t have enough money. And so I work hard to make sure that no kid has to ever hear that. Again. Because that’s total bullshit. When others have it, have the resource. It’s not yours to hoard. It’s yours to share. And it’s just a value. If you don’t have it, let me know. And we’re going to have a frank conversation. So Serve Your City is changing, you know, dramatically, you know, based on what’s occurring now. We were able to easily transition to deal with the COVID response, because we never accepted any government money. We weren’t ever, you know, expecting any foundational support. We didn’t rely upon those systems in the first place. I mean, literally, my cousin asked me did you apply for PPP? I was like, apply for PPP, for what? You know, because everything that we do, and that we did, you know, my job, my skill that I’ve been gifted is, I can get everything for free. I mean, it’s a hell of a skill to have. But it doesn’t really build up a good nonprofit, right? Because we’re not really a nonprofit. We’re only a nonprofit for the white gaze. Let’s be honest about it, you know, only for state recognition. So they leave this Black man and what he’s doing alone, that’s really, I’ll tell anyone that. I’ll be honest about it. It’s only because of the white gaze, that we’re a nonprofit. We’re not really a nonprofit. I said PPP, why would I take money from the government? When I’m trying to build a world not dependent upon the government? Why would I do that? And, and so it just… Our flexibility, our autonomy, we were able to shift immediately to start providing the basics for our people who couldn’t rely upon the government anymore to receive the basics. And I’m very proud. I miss the kids. I said it the other day, it’s, you know, summer, I mean, that’s our time to shine. I mean, we focus on making sure that our kids directly disrupt majority hyper-white spaces. I mean, that’s what we focus on. And, you know, providing, I got a case of peaches in case anybody knows, wants some, but providing a case of peaches just ain’t as sexy to me. And I got a refrigerator full of cabbage. I got tons of cleaning shit, masks, you know. This is not as exciting to me. But it’s necessary, of course, because if you provide our people the basics, then we can build that into making sure that they have the capacity to acquire a political education. And then we can start organizing. And this is how my grandmother did it. Right? This is how the Panthers did it. This is what it looks like. And COVID is horrible. Because here in DC, I mean, Black people are five times more likely to, you know, get COVID and die from COVID. Right. And we know that the disparity of people who will die from COVID are Black and brown people, because they thought they were, of course gonna have to put themselves more at risk, no question. And then the racist medical system that they have to go into is gonna, you know, hurt them even more. So it’s a terrible, terrible, terrible, terrible motivation, or impetus, to go back and innovate the old system. But I keep telling people, mutual aid is nothing but Jim Crow. It’s nothing but Jim Crow, in the sense that Jim Crow forced us to depend upon one another to survive. We grew beautiful flowers during Jim Crow. And we may not have to call it Jim Crow anymore, but those old skills, we need them bad. We need them back. Because this 60 years, 50 to 60 years of co-option, or integration, or incorporation, however you want to frame it, we’ve lost some things. We’ve lost our collective memory that we know how to take care of one another. I’m just talking about Black folks. I don’t know about white folks. Hey, y’all gotta do something. I don’t know. I don’t know. I don’t know. I don’t know, y’all gotta figure some shit out. Y’all got to figure some shit out. But the way that we’ve organized us is that, you know, the white folks who want to be in the mutual aid space where I am, you know, in Ward 6. You know, we have to develop a relationship. You know, I mostly have white folks doing the administration stuff, you know, they’re doing all the techie stuff. You know, all the shit, you know, they’re signing all these petitions and shit, you know. They’re writing letters, all very important things, you know. Things I don’t like to do, you know, all very important things the white folks really love to do. While our Black-led organizations are the ones that are actually delivering the goods and the items to our people. Because in this Jim Crow city, unfortunately, the haves look like me, the haves nots look like me and the haves look differently. And I am not going to have the haves tokenize our people and come in and out, however, they you know, whenever they feel like it, however they feel like it. I have a trust issue. I have a trust issue. And I got to work that out. And then the white folks got to work that out. And that takes time. That’s a relationship. And so we’re a work-in-progress, but while we’re a work-in-progress, I mean, we passed out, you know, tens of thousands of masks. We’ve fed probably 5,000 to 6,000 people. I’m basically you know, we’re doing the work. We’re basically a foundation on the ground. We have given so much money, food supplies, you know, we did our own Black public health campaign, laptops and tablets and hotspots, because of the Jim Crow racist, classist technology divide, you know. So we’re basically a foundation on the ground. And what I’m hoping is that we can organize enough people to do the work. So that I can go after those white people in the foundation space. And that misleadership, Black class in the foundation space, because they’re the next soft target. See, this is always about power. And I want the power for my people to be free. I want us to be able to do what the hell we want to do. Whatever that is. Me, I wanted to be, I mean, I’m trying as Eleanor knows, I’m trying to escape to Jamaica. Okay. I’m trying to escape to Jamaica, and live the person I was supposed to live. So I have to learn how to delegate and pass along to the young people. And so this is, it’s been a beautiful transition for me. Because I get to train up a lot of young people, you know, and pass it along. And it’s time for me to go. Right, Eleanor?

Eleanor

I definitely see you on the beach with a cigar and a drink.

Maurice

Thank you, yes.

Eleanor

So kind of with that, like, does the current crisis give you more or less hope for the future?

Maurice

Oh, I’m so, these young people, I love them so much. Oh, my god. I mean, they have absolutely, they’ve given me 10 years back. Really, I mean, in the last couple of months, they’ve made me feel like, you know, every time I had to be quiet, or bite my tongue or suck in my lip, and take it. Put my head down and bear through it, in the last couple of months, they’ve made all of that worth it. Because they’re not afraid. And I am so proud. I am so proud. And it feels like you know, I’ve been in this game, I guess, you know, 30 years, you know, fighting, you know. And I swear in the last couple of months. I’ve just, I am so proud. And I’m so, I just want to give them as much as I possibly can and give it to them so I can get the hell out of the way. You know, and what I’ll do is I’ll help all of us older people get the hell out of the way. I’ll cuss us older people out and move the hell out of the way. I’m good at that. I’m good at that. I’ll tell them to move the fuck out of the way. We are stopping them with our bullshit, clinging on to something that kills us. There’s been nothing that has occurred in the past that could have prevented George Floyd from being choked out like that in public. From Breonna Taylor being shot in her bedroom, with no one having any accountability to it. And so no one can tell me that they have the answer. But this is the world that we’ve given to these young people. And that’s on us, not on them. And so I don’t want to hear it from anyone over 30, really. I don’t want to hear it. Because we’ve normalized a level of hate and a level of white supremacy that makes us sick. They haven’t. That’s why they’re in the street fighting. So zip it. Zip it. I want to give them everything I can give them. I see Jamaica coming soon. So I am very happy. I am very optimistic. We’ve got the right people. And I don’t know, we’re very blessed to have them. And that includes you. miss Eleanor.

Eleanor

I’m over 30 though.

carla

Oh, you’re young at heart though.

Maurice

Yes, you are. Yes, you are.

carla

That’s beautiful. I also ran a youth. We run arts and Ottomans place that was one of those not nonprofits, but we said we were. Our thing was that most organizations for youth are about getting youth off the streets. And ours was about getting youth on the streets causing trouble. Causing shit, problem. So all this all resonates with me. And people used to always ask, you know, how can I help? And I’d say get the fuck out of their way. Stop blocking them. So you know, you’re speaking my language. And I love it. And thinking about, you know, passing the baton and moving to Jamaica, like, is there? Is there a young person? Or is there somebody that you’ve worked with? That’s in your movements? Who inspires you most? Like, is there one name or is there two?

Maurice

No, there’s no one. I’ve got, you should see my young people. That’s beautiful. I’ve got these young Black sisters, you know, and I’m just putting way too much on them. I tell all these young people, I tell them this. I’m giving this to you transparently. I’m going to overwork you, because I need to make sure you’re ready to do it and do what’s necessary for our people. I’m so sorry that you’re burdened with this, but it is your burden. It is your burden. I have so many. It’s a blessing. And I tell them transparently. You know what it is. Only thing that worries me. There’s a disconnect. So there was there was a shooting last night, up near you. Eleanor. I don’t know if you heard about this.

Eleanor

I did, yeah.

Maurice

There was a shooting last night. And you know, one person was dead. Nine people were shot. We have a lot of organizers up there, where Eleanor is and where the shooting was. But they’re not connected. They’re newcomers or gentrifiers. You know, colonizers. They care. They can tell you all about the policy initiative, they can, you know, scream, defund the police all day and all night. But they don’t have relationships with the people who are directly impacted by these structural tools of oppression that we feel here in Washington, DC. And so they don’t have these community relationships. And oftentimes, the people from the community don’t feel comfortable in these spaces, because they’re not as educated. Because they don’t speak the language. They’re not, quote unquote woke enough and all that bullshit. And somebody’s got to bridge that. So it won’t be me. That’s for the young people to decide. I’m on my way out, lady.

Eleanor

I totally hear that one. This is something that I’ve talked to people about, like when they asked me like, oh, you like you seem to have connected with the people in West Virginia, where you did your documentary. How did you connect with them? And I was like, why are you asking that like they’re a different species or something? There’s fucking poor white folks. Like they’re not aliens. Like, I grew up with poor white folks. And there’s this like misconception that you have to dumb yourself down to talk to them. And I’m like, would you call it dumbing yourself down to speak French? No, it’s just a different way of speaking. And that’s how it is to speak to these people. And it’s like, no one needs to be told what oppression feels like. They just might not be able to say it in like the ‘I got a liberal college degree’ like language that you want them to speak. But they know what it feels like and they don’t want you to talk down to ’em. So yeah, I feel that.

Maurice

Yeah. It’s tough. It’s hard. It’s going to hurt the movement, unless somebody and some people really start addressing it directly. And I think that’s happening. I think mutual aid, our mutual aid work helps on these issues. I think I think the mutual aid work, I think it has an opportunity to do some of that bridging that’s absolutely necessary. I mean, we got to be honest, white people are doing this because they feel badly. We got to be honest about that. Got to say it, man, be honest. But that’s not enough. It’s not enough, not enough. We’re talking about sacrifice and accountability. And true collectivism, you know, which means that your wellbeing is absolutely tied to the wellbeing of your comrade. You know, we have to have a conversation about… a conversation I am willing to have is to our leftist white allies, we’re going to have to have a real talk. We’re going to have to have a real talk, real talk. We got to be in community together. And I was saying this to Eleanor that night. You know, around the turn of the century, when the leftists, Eastern Europeans came and immigrated here, who had already started, you know, kind of their socialist communist political education. And they brought it to the ghettos in Detroit, and Chicago and New York. And here, and in Washington, DC. Our Jewish allies, our Jewish comrades, we shared the same class. We lived in the same communities. We organized together. We were all in the same community. In 2020, we’re not.

Eleanor

So you mentioned like, you know, the need to teach, and, you know, like, ready the next generation, but for your own journey, how do you feel that it’s still evolving? And do you feel like you still have a lot to learn?

Maurice

Oh, yeah. I mean, my learning comes from the young people. I mean, they got these ideas, man. And so, I love it. They’re just so full of ideas. And so I’m growing. I’m growing every day, all the time. I mean, and I get to see a transition that I didn’t think I was going to see. I just, you know, we’re experiencing a level up, you know, in this liberation war. now. Everything is uncertain. Everybody’s responding to uncertainty. And when this first happened, what did my body just naturally do? Because I felt locked in, you know, what I naturally did, I bought a bong. And you know, I haven’t had a bong in like, 30 years. I bought a bong, you know. I started drinking beer again. I haven’t drank beer like this in decades. I reverted back to when my life was, you know, when I was, you know, this smart, but had no security. Right, nothing but a belief that I was gonna make something of myself. You know, I was just riding on belief and hope and faith, but I had nothing in my hands to say that it was going to turn out okay. And that’s crucial, you know, for a little Black boy whose father was locked away, whose country says that you’re going to be locked away or dead or in prison by the time you’re 24. Just by, you know, statistics, feeling that in turning almost 50, and turning 50 this year? Man, I’m so excited. It’s nothing but learning. I actually have common sense, which I didn’t have back then. I have scars from bad experiences, which I didn’t have back then. Did I mention I have common sense? Because I didn’t have any of that back then. So now this is exciting, and you know, Serve Your City and Ward 6, I mean, it’s such a blessing to be able to support our people in this basic, necessary way. To grow it into an opportunity to politically organize. I just want to empower our people not to depend upon that system that they’re being hurt by right now. And what a great opportunity to do that.

carla

You definitely lead with your passionate heart, Maurice.

Maurice

And it comes in sacrifices. I mean, you know, it’d relationships right, Eleanor? Sacrifice personal relationships. I’m so damn hurt. I just, I love our people. And I think this society is willing to sacrifice all of us. And I just can’t allow that on my time. Not without a fight.

carla

Yeah, I guess that would be one of my questions. Seems like you’ve been doing this so long. And how do you how do you ward off burnout or I mean, I’m sure you have moments of burnout, but you keep going, like, what keeps you going? What keeps the spark, the light?

Maurice

You know, it’s the day-to-day balance. And listen, I’m the one who is blessed with the opportunity to provide the support. And so I receive all the, I mean, you know, I, I try to give people a lot. I mean, I do. And, you know, but I’m the recipient, if that makes any sense, you know. I’m the one who is satiated when I’m able to support people. And so, I mean, I work with a lot of young people, you know, and so their energy has saved me all these years. It’s just the little things. It’s just the little things. And I don’t have any choices, by the way. And I hear this stuff about burnout and all this stuff. And it’s true, all of it is true. And I don’t want anyone else to feel it. But again, I remember the people, my grandmother’s mentors, born in the 1910s and ’20s. Do you think they knew of a term like burnout?

carla

No, I’m with you. I always think about working class people like they know burnout, or working poor, you know. But I’ve always associated it with being hurt. Like, yeah, and I went after this, or organizers say they’re burnt out, they’re often needing a break. They’re often, their heart’s being broken or, something’s hurting.

Maurice

That’s absolutely true. And also, my people didn’t work so hard for me to grind myself to the ground and sacrifice everything. I’m not working this hard for the young people I work with to do the same dumb-ass shit that I’m doing. Really, I’m not. And so when I talk about, you know, when you ask me ‘what am I learning?’ I’m learning to also, and it’s a process, but also put myself in the picture in the world that I want to create for these young people.

[music]

Eleanor

Silver Threads is recorded in different places across borders. carla is located in Canada on Squamish, Musqueam and Tsleil-Waututh lands. Eleanor is located here, and they’re usually either in Sweden or on Piscataway land, now known as Washington DC. And our guests join us from around the world. You can find out more about the show and our guests at groundedfutures.com. To learn more about Eleanor’s work, visit artkillingapathy.com and follow her on Twitter and Instagram @activisteleanor. For carla, follow her on Twitter and Instagram @joyfulcarla. You can also reach out to us at [email protected]. And lastly, if you want to support the making of the show, you can donate over at groundedfutures.com Thank you to the Grounded Futures team for supporting us with promotion. All of this snazzy graphics that you see are created by Jamie-Leigh Gonzales. Grounded Futures is a multimedia platform and is produced by carla bergman, Jamie-Leigh Gonzales and Melissa Roach. Post-production audio for our show is done by Eleanor Goldfield. The intro and outro music for our show is a song called “Floodlight” by Eleanor’s former band, Rooftop Revolutionaries. Thanks for listening. And now let’s go rattle thrones and topple empires.

[music]

End of transcript.

_____________________